But the night of the closing, she found herself in the emergency room after vomiting blood. The diagnosis hit as hard as the symptoms: stage 4 cirrhosis of the liver. Her liver was failing.

A long-time drinker, Jennifer had leaned heavily on the habit after her divorce. She kept her drinking a secret, but admits now that a glass of wine was never far away. “I drank and drank and drank, and I drank—without anyone knowing it,” she says.

And then, just when she was making positive changes and taking her story back, her liver “freaked out.”

After her condition stabilized, she was discharged home with an appointment to follow up with a liver specialist. She took another trip to the same emergency room a few weeks later with similar symptoms—this time, she nearly died. Placed on the liver transplant list, she headed home to gain strength and wait for an organ. She followed doctors’ orders, trying valiantly to will herself back to health with good nutrition, vitamins, holistic healing and prayer.

The week before Easter 2018, she took another turn for the worse. Now, in addition to her liver disease, her kidneys were also failing. Her petite body — 5’6” and 115 pounds usually — began to swell. She wanted desperately just to stay home with her family for the holiday, but it became clear that she would not survive the weekend. This time the ambulance headed to a Memorial Hermann hospital in Houston.

That’s when Jennifer’s story shifted.

Jennifer’s struggles had come to the attention of David Ryan Hall, MD, a transplant surgeon affiliated with Memorial Hermann-Texas Medical Center (TMC), through a friend at church after one of those emergency room visits in 2017. But at that point she was under care at another hospital, and there wasn’t much he could do.

Now, she was at a Memorial Hermann facility, and the team from the Transplant Center at Memorial Hermann-TMC was called in for a consult.

Round-the-Clock Intensive Care

When Dr. Hall first saw Jennifer, her weight had swelled to more than 200 pounds from the buildup of fluid from both liver and kidney failure. “She was so ill, so swollen. She couldn’t even walk,” Dr. Hall remembers.

Transplant was her only hope, but the volume of water in her body was putting too much pressure on her heart. They had to reduce that volume through medication, dialysis and teamwork.

Most people who need a liver transplant are not as ill as Jennifer had become, Dr. Hall pointed out. Many patients wait at home for an organ, but Jennifer’s condition had deteriorated to the point where she required round-the-clock care in the intensive care unit (ICU) just to get to the point where she could receive a liver.

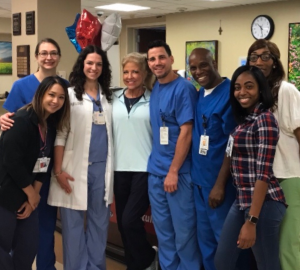

The staff at Memorial Hermann “took care of me like a mother does a newborn,” Jennifer remembers. “I was so dependent on them. I was so heavy, and in so much pain…but they fed me, sat with me, rubbed my arms and told me everything would be okay.”

Jennifer wanted to repay the staff for their kindness—and relieve some of the stress in their days. Trapped in her own body, she may not have been able to move on her own, but she arranged for the delivery of take-out meals to the ICU staff at least weekly during her stay. (Even now on follow-up clinic visits, she’s been known to show up with something for the staff.)

Part of the Team

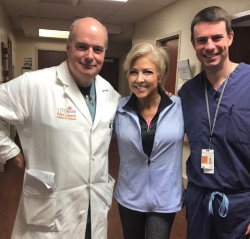

Transplant care is a team endeavor at Memorial Hermann. J Steve Bynon, MD, FACS (director of the abdominal transplant program), Wasim Dar, MD, PhD, and Dr. Hall make up the team that performs liver, kidney and pancreas transplants. The doctors rotate call for the three aspects of transplant care: getting the organ (procurement), placing it into the patient (surgery) and follow-up care (clinic). At Memorial Hermann, Dr. Hall explains, “We provide care that is consistent, 365 days a year. There is never a time when the liver transplant surgeon is out of town.” Patients thrive from that attention to detail and consistent care, as demonstrated by Memorial Hermann’s stellar transplant outcomes.

Through her four months at Memorial Hermann and her follow-up care afterwards, Jennifer has gotten to know all the physicians on the team—and has observed their strengths. Dr. Bynon is precise and confident: “He knows what to do, and he does it,” she says. She describes Dr. Dar as a quiet genius, the conductor in the orchestra. Dr. Hall stands out with his compassion and caregiving, she says.

The transplant team extends beyond the physicians to the nurses and staff of the ICU as well as the patients and their family members. With her father, 10 siblings and adult son all involved in her recovery, Jennifer came with a full team of her own, too.

Hard Road to Happy Outcome

Hard Road to Happy Outcome

Jennifer was in good hands, but she wasn’t out of the woods. According to Dr. Hall, many patients at this stage of liver failure develop brain swelling or respiratory failure and die before transplant is possible. But Jennifer got stronger and moved up to the top of the transplant list. When a liver became available for her, Dr. Dar went and retrieved the organ, Dr. Bynon did the transplant and Dr. Hall assisted.

“When patients are that ill, recovery can be difficult,” says Dr. Hall.

Some can make it through the transplant and still not survive. But since getting her new liver in May of 2018, Jennifer has been pretty much unstoppable. She spent barely a week in in-patient rehabilitation, then headed home to the house where her son had unpacked and readied for her arrival. She’s now planning her return to work and her travel itinerary of visiting family and friends around the country.

Jennifer thinks it’s important to tell her story, even the part about the role her drinking played in her condition. Hearing those stories can help lead people to the help they need. “Everyone who is a recovering alcoholic has a story,” she says. “The hope is that my story could help one person to not take it to the extreme, to stop drinking and take care of their liver.”