At the end of a family vacation in Snowmass, Colorado, 17-year-old Clay “Tato” Stanley was seriously injured in a snowboarding accident. “They were doing jumps, and Tato lost control on the landing and was immediately paralyzed,” Tato’s mother, Alice Stanley says. Tato, an experienced snowboarder with no previous mishaps, remained fully conscious after the accident. He was stabilized at Aspen Valley Hospital and flown to Swedish Medical Center in Denver, where he underwent a C5-C6 spinal fusion with instrumentation. Two weeks later, he was transported by air ambulance to TIRR Memorial Hermann in Houston.

At the end of a family vacation in Snowmass, Colorado, 17-year-old Clay “Tato” Stanley was seriously injured in a snowboarding accident. “They were doing jumps, and Tato lost control on the landing and was immediately paralyzed,” Tato’s mother, Alice Stanley says. Tato, an experienced snowboarder with no previous mishaps, remained fully conscious after the accident. He was stabilized at Aspen Valley Hospital and flown to Swedish Medical Center in Denver, where he underwent a C5-C6 spinal fusion with instrumentation. Two weeks later, he was transported by air ambulance to TIRR Memorial Hermann in Houston.

“When he arrived in January 2012, Tato had some slight sensation in his legs but no movement in either his legs or hands,” says his physiatrist Matthew Davis, MD, medical director of the Spinal Cord Injury Service at TIRR Memorial Hermann and an assistant professor of physical medicine and rehabilitation at McGovern Medical School at The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston (UTHealth). “We had no idea if he would be one of the lucky few who regain the ability to walk after this type of cervical injury. Initially, we focused his therapy program on waking up sensation in his legs and on teaching him the basics of caring for himself.”

Tato also learned how to operate a power wheelchair. “Some patients resist learning wheelchair skills because their ultimate goal is to walk again,” Dr. Davis says. “We tell them that even if they do walk, it will take a while to regain those skills, so they need to learn how to use a wheelchair properly. Tato had a great attitude about it. He did everything we asked him to do as well as he could. From the beginning he worked really hard.”

Tato spent a month in the hospital in phase 1 rehabilitation. “Usually about this time we notice that the cervical collar starts getting in the way of progress in therapy,” Dr. Davis says. “To conserve our patients’ insurance dollars, we send them home to wait for the collar to come off, which is usually about three months after the surgery,” Dr. Davis says.

By March 2012, Tato was back at TIRR Memorial Hermann, ready to begin the next phase of inpatient rehabilitation. He had slight movement in his legs – potential strength his therapists could build on.

In April, he was accepted into the NeuroRecovery Network’s locomotor training program at TIRR Memorial Hermann, and his parents found an apartment in Houston. For the next year and a half, Alice and Monty Stanley took turns making the three-and-a-half-hour drive with their son from their home in Longview, Texas, on Mondays, returning home on Fridays.

A cooperative network between the Christopher and Dana Reeve Foundation, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and six cutting-edge rehabilitation centers, the NeuroRecovery Network (NRN) provides and develops therapies to promote functional recovery and improve the health and quality of life for people living with paralysis. The NRN’s goal is to translate the latest scientific advances into effective, activity-based rehabilitation treatment, and its primary activity-based intervention is locomotor training, which builds on advances in scientific understanding of neuroplasticity – the ability of neurons in the nervous system to develop new connections and “learn” new functions – and the role the spinal cord plays in controlling stepping and standing. Locomotor training works to awaken dormant neural pathways by repetitively stimulating the muscles and nerves in the lower body through hour-long sessions in which patients are suspended in a harness over a treadmill while trained therapists move their legs and body to simulate walking. Treadmill training is followed by 30 minutes of therapy over ground; the sessions are held five days a week.

Like Tato, participants in the NRN become part of a network-wide database in which therapists and researchers collect information about the progress of each patient. By analyzing the information, researchers at the NRN are able to measure program outcomes accurately.

With a spinal cord injury above T10, some movement in his legs and his ability to tolerate body weight-supported treadmill training, Tato was the ideal candidate for locomotor training. Physical therapist Denise Liau, PT, DPT, charted his progress for more than a year.

“When Tato started in the program he was using a manual wheelchair for mobility,” Liau says. “By July 2012, after just three short months of locomotor training, he was able to walk about 15 minutes with a rolling walker. From then on it was full speed ahead.”

By August, he was walking an hour a day. In September and October, he was walking two hours a day, and in November, he progressed to three hours a day with a rolling walker. In January 2013, he made a huge leap forward and was using his rolling walker primarily, spending only one hour in his wheelchair. He also increased his activity with friends and made progress in everyday functional activities. He maintained this level of mobility from February 2013 until his discharge in May. He also progressed to walking with bilateral forearm crutches.

Liau describes Tato as “positive, very motivated and extremely hardworking. He has an all-around great attitude and never lets anything hold him back. He’s very determined and never struggles with self-limiting thoughts.”

With significant progress under his belt, Tato enrolled in his first semester at The University of Texas at Austin, where he had planned to go before the accident. “He lived in an apartment with two friends and took classes,” Alice Stanley says. “He got a permit to drive and was pretty independent but it was a huge undertaking. He walked with his crutches across the campus in every type of weather, even with Austin’s terrible summer heat. At the end of the semester, he could tell that his recovery was at a standstill and decided to go back into therapy.”

Tato returned to Longview, where he did outpatient therapy and took online courses at nearby Kilgore College. “Again it was too taxing to do school and therapy,” Stanley says. “He considered transferring to Texas A&M, but by fall 2015, he was at the four-year mark after his accident and decided he wanted to get as much out of therapy as possible. About that time, we got a call from TIRR Memorial Hermann about a new NRN upper-body program, so we moved him back to Houston.”

Tato enrolled in the NeuroRecovery Network’s upper-extremity research study in October 2015. “Regaining strength in the upper extremities is an underappreciated part of recovery from spinal cord injury,” Dr. Davis says. “Immediately after the injury most patients say they want to walk again. But if you ask those who have lost the use of their legs and hands about their feelings two years later, most people will choose the ability to use their hands.”

Tato is the first patient to participate in the NRN’s upper-body research program at TIRR Memorial Hermann. “Our goal is to facilitate upper-extremity recovery to achieve normal movement patterns,” says Kathryn Nedley, OTR, OTD, “The program is very structured, with a protocol designed to reprogram the nervous system to function in a way that’s similar to the way it functioned before the injury. As part of his initial recovery from injury, Tato developed some habits that made him more independent at the time, but his movements were not part of a recovered movement pattern. So we’re using electrical stimulation to reach the muscles in his shoulders and hands, and to stimulate all the way back to the level of the spinal cord to allow him to move in the correct way. He’s making progress and we’ll keep going forward with the study as long as he continues to benefit. Walking is still important to him, but he knows he needs to be able to use his hands to be independent. That’s how we interact with the world.”

Nedley says Tato has a strong awareness of what his body is currently doing and what it should be doing. “He learns very quickly and has figured out how to make his body do what he wants it to do,” she says. “He’s put a lot of effort into educating himself about his body and injury, which has helped enormously with his recovery.”

Because of his participation in the upper-extremity study, he also qualified for the NRN locomotor program and started back on the treadmill. “For my legs I use a harness and practice walking on a treadmill for an hour and then do 30 minutes of over-ground activity,” he says. “We’re working on my gait pattern to help prevent future issues with arthritis. For my upper body we’re using an FES bike, with electrical stimulation to stimulate the spinal cord. It’s going pretty well. It’s helping a lot with my posture and hand function.”

Dr. Davis observes that the great unanswered question in rehabilitation after spinal cord injury revolves around prescribing the proper dose. “How long do you work with patients to get them walking again? Back in February 2012, Tato had just a little bit of movement in his legs,” he says. “Most patients who have muscle scores of only 1 out of 5 in a few leg muscles at two months after the injury do not improve dramatically. For him to be walking is pretty unusual. It’s not so rare that I would call it miraculous, but we do know that if it weren’t for the NeuroRecovery Network and the intensive therapy Tato has done, it’s unlikely that he would be walking now.”

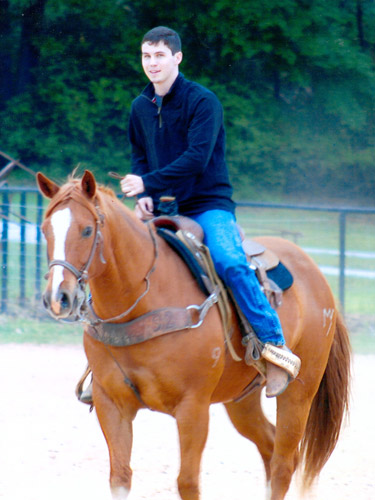

Tato lives in an apartment not far from TIRR Memorial Hermann and spends most of the day walking with the help of his forearm crutches. A former team roper, he rides horses for pleasure when he’s home on the weekends.

“He’s very independent,” his mother says. “I try to go to Houston once a week to help with the laundry and catch up on grocery shopping. I’m just still being a mama. He can go to the grocery store and do everything himself. It just takes longer. “He’s very disciplined, his mother says, he gets up early and does his exercise and stretching routine. He told us he did a rock-climbing wall not long ago. He’s a little miracle. We believe the prayers from family, friends and strangers from all over and God’s grace led and are still leading his recovery.”

Monty Stanley says he’s very proud of their son. “He’s giving his best effort and as long as you do that, you are a success,” he says.

Tato describes his time at TIRR Memorial Hermann as “hard to sum up. Overall it’s been an incredible experience that continues to go smoothly,” he says. “I couldn’t ask for a better place to be or a better environment to recover in. They are all incredible people who just made it very easy and encouraged me to work hard and improve as much as I can – and gave me the opportunity to do that. I have a pretty long list of people to thank.”

“We know that some people who come to TIRR Memorial Hermann with no movement in their legs or hands have the potential to walk again,” Dr. Davis says. “It’s always rewarding when we see it happen. It’s a team effort. The patient did his part, and the therapists did their part. Tato benefited from a supportive research community, a supportive family and a good group of friends. All of these people together helped him accomplish something that was statistically improbable.”

Contact Us

If you have questions or are looking for more information, please complete the form below and we will contact you.

Nationally Ranked Rehabilitation

For the 36th consecutive year, TIRR Memorial Hermann is recognized as the best rehabilitation hospital in Texas and No. 2 in the nation according to U.S. News and World Report's "Best Rehabilitation Hospitals" in America.

Learn more about TIRR Memorial Hermann rankings