Christine Dugger’s first maternal-fetal medicine appointment in Sacramento, California, went well. “The second appointment, at about 13 weeks of pregnancy, was a complete shift,” she says. “We had the ultrasound done before the physician came in, and the tech was quiet. When the doctor came in, she did a rescan. She said she wasn’t visualizing Baby B’s bladder or kidneys, but then she said maybe it’s too early. That didn’t feel right to me based on my experience with prior pregnancies, and also because she could visualize those organs on our other twin. We knew the diagnosis of renal agenesis was likely to be fatal, but it was early in the pregnancy and we still held out hope that his kidneys were too small to be visualized on ultrasound. We hoped that this was something that could be treated either in utero or after his birth.”

Babies without kidneys do not produce amniotic fluid, which has a serious impact on lung development. Lack of amniotic fluid is a symptom of twin-twin transfusion syndrome (TTTS). Identical twins that share a common placenta usually have blood vessel connections between the two fetuses. In about 15% of these pregnancies, twin-twin transfusion occurs when the blood vessels produce an uneven sharing of blood, with blood from one twin (the donor twin) pumped to the other (recipient) twin. When this occurs, the heart of the donor twin does extra work to support the recipient twin, who gets too much blood. The donor twin doesn’t get enough.

With treatment, TTTS can resolve and amniotic fluid levels can regulate. “In our case we had two possible causes for Rand’s (Baby B’s) lack of amniotic fluid: renal agenesis or TTTS,” Dugger says. “The first was automatically fatal; the other potentially fatal for both twins, but treatable with the right intervention. We asked for an immediate referral to a tertiary care center.”

Referral to San Francisco

At Christine Dugger’s request, her maternal-fetal medicine specialist in Sacramento referred her to the University of California, San Francisco Medical Center, an hour-and-a-half drive away. After the first appointment, doctors there confirmed that Rand suffered from renal agenesis and not TTTS. “It was devastating,” she says. “I remember driving home across the San Francisco Bay, looking out at the water and thinking I’d never felt more alone.”

After the first appointment, Christine was seen twice a week to monitor other issues with her twins. While Crosby (Baby A) appeared to be developing normally, Dugger’s physician team said that there was a high probability that Rand would die in utero, given his diagnosis and other issues that were appearing. When one twin dies in utero, the shared blood immediately goes to the other twin, creating a stroke-like effect that can lead to neurodevelopmental problems for the surviving twin—or death.

“We were in this state of constant monitoring and never knew what was going to happen from one day to the next,” she recalls. “One of my coping mechanisms for processing what we were going through was research. I needed to educate myself, but more than anything, I was willing to fly anywhere in the world if someone could help Rand.”

Dugger went into full research mode. She emailed and called researchers in Japan, South Korea and Belgium as well as the top maternal-fetal medicine centers in the United States. “I found their names through ResearchGate, and asked them to share their research with me because I couldn’t get access without medical credentials,” she says. “I was collecting a body of research so I could understand the big picture, as well as be informed about all treatments available—not just the ones offered to me. The primary issue I researched was exploratory treatments for Rand’s lack of amniotic fluid. I thought if we could find a way to mimic the amniotic fluid a baby normally produces, it would be possible for his lungs to develop. If we could do that, Rand might be a candidate for peritoneal dialysis at birth until he could receive a kidney transplant. It was a pie-in-the sky hope that wasn’t to be.”

At the same time, Dugger was coming across research describing a different type of transfusion syndrome affecting identical twins. Twin anemia polycythemia sequence (TAPS) is a rare form of twin-twin transfusion syndrome caused by chronic blood loss between the fetuses through tiny vessels in the placenta. She compared the research she was collecting with Rand and Crosby’s twice-weekly ultrasound reports.

“I came across it almost by accident,” she recalls. “As I read the TAPS papers, I kept coming back to the term “middle cerebral artery Doppler (MCA),” and in the back of my mind recalled there being a discrepancy between Rand and Crosby’s MCA readings on their ultrasounds. I’m a datadriven person, and I put a lot of weight in science, so I started plotting the twins’ MCA results in an Excel spreadsheet to see if I could recognize any patterns.”

As she plotted data over eight weeks, she saw that Rand and Crosby’s MCA Doppler readings continued to trend apart. MCA blood flow can be measured during an ultrasound, and anemia is suspected if the blood flow in one of the MCA fetal vessels of the brain is increased by a certain level.

Based on the MCA Doppler readings, Rand was severely anemic. As he became more anemic, new issues showed up in the ultrasound reports. “One week he had fluid around his heart. The next week he was suspected of selective intrauterine growth restriction. Another week the doctors were concerned that he had an enlarged vessel in his brain,” she says. “All the while, the MCA readings continued to be alarmingly discordant, and gradually it became clear to me that our twins had TAPS.

“It was like we had been struck by lightning twice. By then we knew that Rand would not live after birth. In addition to Rand’s fatal anomaly, Crosby was now faced with a life-threatening situation,” she says. “My otherwise healthy baby was severely polycythemic, with too much blood, and his life was now at risk without immediate intervention.”

The interventions for TAPS are the same as for TTTS—fetoscopic laser ablation, an intrauterine surgery that stops the blood flow between the problematic blood vessels in the placenta, or selective termination of one twin. “My doctors told me they did not perform laser ablation for TAPS, but could offer selective termination. To us, selective reduction was the imposition of guaranteed risk—death for Rand and risk of death for Crosby. We were not willing to impose guaranteed risk on either baby, so I asked them to refer me elsewhere.”

The Search for a Physician Who Could Intervene

Dugger knew she wanted fetoscopic laser ablation of the communicating vessels between Crosby and Rand, a minimally invasive procedure that would stop the abnormal fluid exchange by cauterizing blood vessel connections. “Successful laser ablation would be curative for the TAPS that was threatening both of their lives and ensure that each baby had his own blood supply. Should Rand pass away before birth from his other complications, his death would no longer pose the same threat to Crosby,” she says.

An internet search led Dugger to physician-scientist Ramesha Papanna, MD, MPH, an associate professor in the division of Maternal-Fetal Medicine at McGovern Medical School at UTHealth. Dr. Papanna, who is affiliated with The Fetal Center at Children’s Memorial Hermann Hospital, is internationally recognized for his research on improving outcomes following fetal intervention and investigating methods for the prevention of preterm delivery. He is actively involved in fetal intervention for twin-twin transfusion syndrome, fetal spina bifida and other fetoscopic and needle-guided in utero procedures.

“I was on the phone with one of the nurses at The Fetal Center right away, and they called me the next day and asked us to come to Houston. I talked with Dr. Papanna after he had reviewed my medical records. He said, ‘Yes, this is serious and there is an intervention. How soon can you get here?’”

Fetoscopic Laser Ablation for TAPS in Houston

On Friday morning, Dugger called her mother and asked her to fly to Houston, while her husband remained at home with their daughters. “Although Blake wanted to be with me, we decided that our kids needed normalcy. I told the girls I was going on a work trip, packed some yoga pants and a sweatshirt, and left for the airport,” she says.

On the way to the airport, she called her OB/ GYN to ask for an urgent referral to Dr. Papanna and Children’s Memorial Hermann Hospital. “When I got insurance approval, I understood how privileged and lucky I am, and that other mothers’ inability to make the choices I was making is rooted in inequality. It saddened me that women have to make life or death decisions based on financial concerns,” she says.

In Houston, they met Dr. Papanna and one of his ultrasound techs. “At that point, TAPS had progressed since my last ultrasound in California a day or two before. In TAPS Stage 2, one twin is clearly polycythemic and the other is anemic,” Dugger says. “By Stage 4, the anemic twin is hydropic, with extreme swelling of organs caused by the buildup of fluids in tissues. That’s what we had the day we got to Texas.”

“TAPS is a rare and misunderstood condition that puts the lives of both twins at risk,” Dr. Papanna says. “We had to act quickly to save Crosby’s life.”

He gave her two options: selective termination or laser ablation. The following morning he performed a minimally invasive fetoscopic laser ablation to close the blood vessels connecting Crosby and Rand, safeguarding Crosby until delivery.

“Dr. Papanna treated me with such respect, and he was genuinely approachable, yet I was in awe of him,” Dugger says. “Here is this distinguished physician who is changing the lives of so many families, and he’s with me in a hospital room at 9 p.m. on a Friday night. The next day we’re in surgery receiving the intervention I had sought so desperately.”

During the procedure Dr. Papanna took photos that provide a stunning visual representation of TAPS. “Rand, the anemic twin, was almost iridescent. You could see beneath his skin. He was transfusing all his blood to his brother. Crosby was deep maroon because of the thickness and volume of blood. Dr. Papanna said we were within days of losing Rand and possibly both babies,” she says.

After surgery, an ultrasound showed that both babies were living, and that Rand was no longer anemic and Crosby was not polycythemic. “In a perfect world, I wanted to spend the rest of my pregnancy in Houston, where I felt like I would receive the best care, but intellectually, I understood that now, post intervention, it was a waiting game.”

Dugger flew back to California Sunday night. “I was only 22 weeks pregnant at this point, yet with everything our twins had gone through, it felt like a lifetime,” she says.

Giving Back and Paying It Forward

Dugger transferred her care back to Sacramento and went into labor at 31 weeks. She was hospitalized for eight days after her water broke. When her maternal- fetal medicine team was unable to delay labor any longer, she delivered Rand and Crosby by C-section.

“Crosby was born first and Rand a minute later,” she says. “We had been operating under the notion that Crosby was the healthy baby and Rand, the sick baby, but to our surprise and horror, Crosby was born pale and mottled and didn’t cry. They had to resuscitate him and immediately transfer him to the NICU. We knew Rand would not live long after birth due to his renal agenesis and the resulting lack of lung development. After hours of consultation with various care providers, we had decided in advance to offer comfort care to Rand. The nurses gave him to me right away while they finished surgery. Rand lay on my chest the entire time, except for when my husband held him. I’ve never said as many ‘I love yous’ as I did in those 58 minutes.”

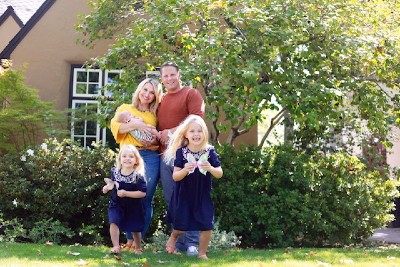

As he lay on his mother’s chest, the hospital chaplain baptized him before he passed away. “I wanted to be certain that Rand never experienced pain. Palliative care for terminal infants ensured that,” Dugger says. “After his death, Rand stayed with us for the next 48 hours, and I held him the entire time. Those hours, the only ones I have with Rand, are permanently burned into my memory. Our girls came to the hospital the morning after his birth to meet their brothers. We all went to the NICU where Crosby was, and that is our only photo of all six of us.”

After Dugger was discharged and the family said goodbye to Rand, she spent the next six weeks in the NICU with Crosby. Those six weeks gave her perspective and clarity on what to do next.

“After experiencing the NICU myself and seeing what other parents were going through, we wanted to do something for Rand and at the same time ensure that the moms who come after me have access to research and interventions,” she says. “Waiting for an intervention can be, and very often is, deadly. We also wanted to make sure the research Dr. Papanna is doing is continued. We were stunned not only by his resume but also by his human kindness. He treats people like people, not subjects or opportunities. My husband and I will do anything to keep TAPS at the forefront of medical research, and supporting Dr. Papanna is one way we can ensure that.”

A few days after the twins were born, the Duggers created the Rand Francis Dugger TAPS Research Memorial Fund at McGovern Medical School to raise funds to further Dr. Papanna’s work. In 2019, they founded the Rand Francis Dugger Foundation with the goal of raising money for Dr. Papanna’s research and funds to support families going through complicated twin pregnancies.

“We’re not limiting support to TAPS, but plan to offer it to anyone experiencing a complicated twin pregnancy who needs a higher level of care and for whatever reason can’t access it,” she says. “The foundation is an important part of our recovery process. I don’t want to say heal because I don’t think you ever heal from the loss of a child. Rand is a part of our world and is with us every day.”

The Duggers incorporate Rand into their lives every day through photos, bedtime prayers and conversation. “My five-year-old daughter will say this: ‘I have three brothers and sisters but only two are here. Rand is with us too, but in heaven.’ We don’t hide our grief. This experience has given us an opportunity to explore our feelings and discover that you can feel happy and sad at the same time. We take advantage of every opportunity to honor Rand. I’m so proud of how our kids have taken on such big adult issues and are figuring out really beautiful ways to process and live with them. It’s important to us that our kids and the world know that Rand was real and Rand was magic.”

To contact The Fetal Center at Children's Memorial Hermann Hospital, please fill out the form below.

If you are experiencing a medical emergency, call 911 or go to the nearest emergency room.

If you or someone you know needs support from the Suicide and Crisis Lifeline, call or text 988.

Located within the Texas Medical Center, The Fetal Center is affiliated with McGovern Medical School at UTHealth Houston, UT Physicians and Children’s Memorial Hermann Hospital.